Jamie Kasuboski, Partner at Luma Group

There are many perceptions of what a venture capitalist (VC) is. In the biotech space, VCs are enigmatic because many of us never imagined becoming VCs, and many future VCs might have no idea they’re headed down that path either.

My story, like many in biotech, started with a passion to help sick people. I was fortunate to discover my passion at the age of six, when I told my parents that I wanted to be a genetic engineer. I didn’t fully understand what that entailed, but the film Jurassic Park sparked my curiosity. I was fascinated by the idea that nature had invented biological Legos called DNA that could be assembled to create humans, sea slugs, bananas, bacteria, mold, and, most intriguingly, entirely new life forms.

Less than two decades later, I received my PhD in Molecular and Cellular Biology. I loved deciphering nature’s clues and genetic codes to figure out the “how” and “why” in nature’s playbook. However, I didn’t yet know how to translate this knowledge from the lab into life-saving therapies. I continued my research journey post-PhD and eventually landed an industry postdoc position at Pfizer. At Pfizer, I soaked up every fact, lesson, piece of jargon, and process required to take an initial discovery and turn it into a drug. At this moment, something clicked for me: my true passion wasn’t just making discoveries; it was figuring out how to transform those discoveries into medicines capable of helping patients. My time at Pfizer also made it clear that I wasn’t ready to join an organization as large as Pfizer long-term. Thankfully, after years of trying different career trajectories and with the help of some great mentors, it became clear that biotech venture capital uniquely aligned both my personal goals: contributing to life-changing therapies, and professional goals: being able to earn a living while pursuing my personal passion.

As they say, “Do what you love, and you’ll never work a day in your life.”

July 2025

Introduction: Venture Capital as the Lifeline of Biotechnology

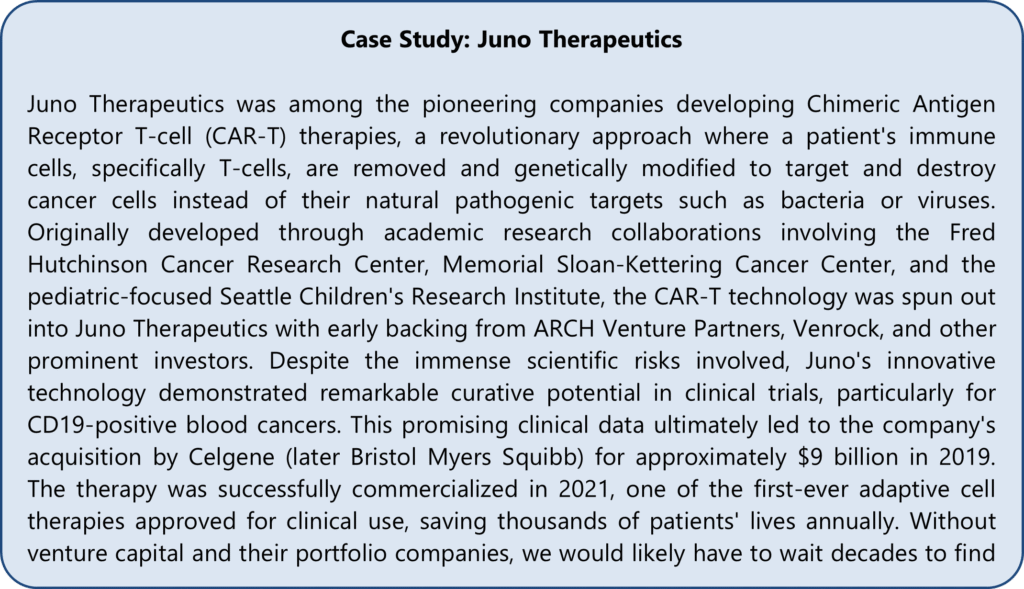

Translating laboratory discoveries into lifesaving treatments for patients is lengthy, requires massive amounts of capital, and is an extraordinarily challenging journey that is mired in constant failures and setbacks. It requires collaboration across multiple stakeholders, from academic researchers, biotechnology companies, and contract research organizations to regulators and pharmaceutical companies. Unlike other sectors, such as technology or manufacturing, biotech innovation rarely progresses within a single organization. Instead, technologies pass through specialized ecosystems and subsectors, undergoing numerous collaborations and handoffs along the way. Additionally, unlike the tech and manufacturing sectors, which scale by repeatedly iterating the same products, biotech and pharmaceutical companies must continuously innovate or acquire innovation due to IP lifecycle constraints. With all these challenges and transitions, venture capital has emerged as a critical niche for shaping and driving this complex process by uniquely tolerating the industry’s substantial financial demands, prolonged timelines, inherent uncertainties, and high failure rates.

Investing in biotechnology is not for the faint-hearted. The investment characteristics are poorly matched to traditional financial institutions like banks, later-stage private equity, and public equity markets, which favor shorter investment horizons and lower-risk ventures. Without substantial funding on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars, these discoveries and innovations will never translate into life-saving treatments. Venture capital firms provide the lion’s share of this critical funding, uniquely equipped with the expertise, alignment, capital, and passion, defined here as the endurance to persist over time, not just enthusiasm, to bridge the risky gap between discovery and clinical development.

A Brief History of Drug Development and the Relationship with Biotech VC

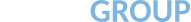

Drug development historically involved large pharmaceutical companies undertaking extensive internal research and development, characterized by decades-long timelines, massive investment requirements, and high failure rates. In the 1970s and 1980s, the emergence of biotechnology, particularly the groundbreaking ability to genetically engineer proteins, revolutionized drug discovery. Biotech startups leveraged academic science and nimble innovation to drive new therapeutic breakthroughs, shifting the paradigm from traditional pharma-dominated R&D to a more collaborative and innovative ecosystem. The rapid rise and success of these startups hinged significantly on venture capital contributions, which provided essential early-stage, patient capital to overcome high-risk barriers and bridge the gap between academic research and commercialization.

Together, VCs, researchers, and entrepreneurs brought transformative innovations, such as monoclonal antibodies, gene therapies, RNA-based technologies, and others to market. This laid the groundwork for modern pharmaceuticals and reshaped the slow-moving, conservative market into the innovation-driven, dynamic ecosystem it is today, saving billions of lives in the process.

Figure 1: Notable Examples of VC-Driven Biotechs.

The Innovation Funding Gap in Biotech

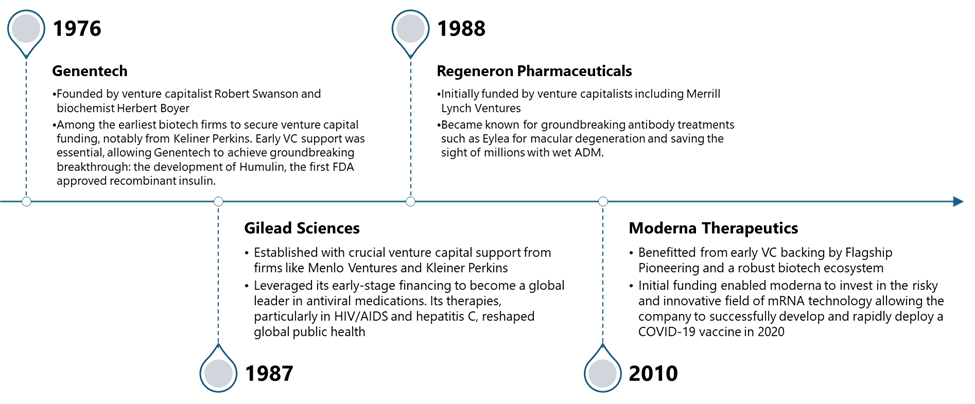

Typically, it takes over a decade and billions of dollars to guide a promising discovery from initial research through clinical trials and ultimately into the market.1,2 Complicating matters further is the phenomenon known as “Eroom’s Law” (Figure 2), highlighting the troubling paradox that, despite technological advances, drug discovery productivity has steadily declined, resulting in escalating costs and diminishing returns.3,4 Over recent decades, the average cost of successfully bringing a new drug to market has surged dramatically, surpassing $2 billion per approved drug (depending on who you ask).5,6

These interrelated complexities have widened the innovation and funding gap: while groundbreaking academic research continues to flourish, translating these discoveries into viable commercial products has become increasingly expensive. This rising cost has significantly squeezed traditional pharmaceutical companies, resulting in an intensification of their dependency on external innovation and reducing internal R&D spend. Over the past two decades pharmaceutical companies have started to play an essential role in the clinical and commercial success of emerging therapies, serving as licensors that guide innovative technologies through the final stages of development and onto the market.

Biotechnology companies, whether private or public, often lack the substantial capital, specialized expertise for late-stage clinical trials, and the robust infrastructure required for successful commercialization. As a result, biotech firms commonly out-license or sell their assets to pharmaceutical companies, leveraging pharma’s financial resources and established commercial pathways to bring new therapies to patients’ bedsides. Influenced by Eroom’s Law and economic pressures, pharma companies have grown more conservative, preferring to wait longer before adopting new technologies, effectively becoming gatekeepers for the commercialization of potentially life-saving innovations.

Figure 2: Eroom’s Law depicted by illustrative historical regression of significant increase of drug discovery and development.

Source: Benchling.

It is precisely at this juncture of financial and scientific uncertainty that biotech venture capital plays an indispensable role. Passionate biotech venture capitalists actively embrace these early-stage challenges, investing precisely when others shy away to provide the bridge between groundbreaking scientific research and commercial viability. The importance of this funding model cannot be overstated; venture capital-backed companies have consistently delivered transformative therapies that shape modern medicine, and without them and their portfolio companies, the industry would quickly decline to a fraction of its size.

Venture capital support is not merely financial; it’s a strategic enabler of groundbreaking medical advances that significantly enhance human health outcomes. Through careful, informed, and visionary investments, biotech venture capital fuels innovation pipelines, enables scientific risks, and ensures that transformative ideas are not trapped in laboratories but rather brought effectively to the patients who urgently need them.

Pulse on the Current Market: When Enthusiasm Outpaces Passion

The rapid exit of generalist funds left hundreds of biotech companies facing financial strain, with low cash reserves and short runways, forcing many to scale back or shut down. This large capital void either needs to be filled by investors, which is unlikely given the sheer scale of capital needed, or there will be another market correction, which will entail more shutdowns, trade sales, and M&A opportunities. The mismatch between high burn rates and the long timelines needed for meaningful value inflection is pushing many promising companies into survival mode. Despite short-term pains, this correction has created compelling opportunities, as high-quality companies trade at steep discounts, offering attractive entry points for experienced investors with fresh capital and limited exposure to prior overvaluations.

Biotech capital markets are cyclical and highly sensitive to broader economic shifts, as seen during the COVID-19 era when the XBI, the S&P’s biotech index, nearly doubled in under a year, attracting trillions in capital. This influx, driven largely by generalist investors that lacked the deep understanding required for biotech investing, fueled innovation, accelerated drug development, and inflated valuations. But it also tipped the balance away from fundamentals. When immediate returns failed to materialize, many of these investors quickly exited, redirecting capital to areas like technology, triggering an abrupt market correction that disrupted the biotech ecosystem and led to the recent downturn.

Biotech VCs: The Sherpas of Innovation

Biotech venture capitalists provide more than financial resources. They serve as skilled sherpas, guiding startups through the challenging journey from early discovery, through clinical development, and ultimately to commercialization. Like Tenzing Norgay, the legendary Nepalese-Indian sherpa who helped Sir Edmund Hillary summit Mount Everest in 1953, the best VCs help startups navigate difficult terrain, carry critical burdens, and stay oriented toward the summit. They bring not only capital but also specialized experience, expansive networks, and strategic insight to each stage of a company’s evolution. So, pick your investors wisely.

VCs also fulfill an essential role as aligners. Biotech startups move through distinct phases, each with different personnel, structures, and missions. VCs ensure continuity. Moreover, effective VCs act as amplifiers, extending a company’s reach and influence within the broader ecosystem. This involves connecting startups with capital sources, facilitating interactions with pharmaceutical stakeholders, advocating externally to enhance the company’s visibility and reputation, and other critical processes.

Above all, the most distinguishing trait of the best biotech VCs is their deep-rooted passion. Many have years or decades of firsthand experience in research laboratories, biotech startups, or pharmaceutical companies, giving them an enduring resilience and ability to maintain unwavering enthusiasm despite the setbacks endemic to biotech innovation. This passion transcends mere enthusiasm; it embodies the capacity to persist through great adversity, remaining committed to the ambitious goal of bringing groundbreaking science to patients in need.

This mission requires VCs to be hands-on, guiding their portfolio through diverse challenges. With dozens of companies under management, VCs must tailor their guidance to each one. This demands not just expertise but time, attention, and strategic dexterity. As VC firms scale, managing their portfolios becomes more complex. Biotech investments often span decades, meaning a single VC firm may find itself managing multiple funds (often two to five at once), each with its own portfolio, LP base, and strategic objectives. The burden of guiding multiple companies across different stages while maintaining internal coherence stretches firms’ bandwidth and heightens the risk of misalignment.

It can be easy to overlook that venture capitalists operate their own business too. In addition to providing tailored support and resources to numerous portfolio companies, VCs must fundraise, manage investors, and oversee firm-level operations. Balancing these dual roles, shepherding others while running a firm, is an often-overlooked challenge. Additionally, VCs are still groups of people that can be prone to errors in decision making, risk calculation, or several other human shortcomings. The best biotech VCs understand this and try their best to stay aligned to fundamentals and remain disciplined even when others are not. In short, they try to over-index on passion to help patients versus chasing short-term returns with enthusiasm.

Built for Biotech, Equipped for Impact

The world of biotech investing is as diverse as the companies and people who make up the industry. Historically, the most successful biotech investment firms have not been generalists, but specialists whose passion and focus mirror those of the scientists and entrepreneurs driving innovation. Most of these biotech funds take specialization even further, focusing their skills and strategies on specific niches within the broader biotech ecosystem.

We founded Luma Group with these same guiding principles, tailoring our strategy explicitly for the biotech industry and our portfolio. One of our initial decisions was to align our fund’s capital cycle with biotech product development timelines. Specifically, we launched a 15-year fund rather than the traditional 10-year structure. This choice reflects the reality that biotech development cycles often require more time than technology or other sectors and forcing a 10-year investment horizon onto biotech would be fundamentally mismatched. At the heart of our philosophy is a simple, unwavering belief: if we do our job, fewer patients will suffer tomorrow. Guided by this North Star, we set out to build a firm uniquely positioned to achieve such an ambitious goal.

Given the highly regulated and empirically driven nature of the biotech sector, it should come as no surprise that the greatest predictor of success is rigorous, accurate science. Amid all the uncertainties, getting the science right is predominantly about running the correct experiments informed by historical data. This principle has shaped a key mantra within our group: “Better data leads to better decisions, which leads to better outcomes for patients.”

This mantra is what guided Luma Group to establish a dedicated research division within our funds, supported by dozens of KOLs and advisors, from former pharmaceutical CEOs and top regulatory officials to PhDs and postdoctoral researchers. The breadth and depth offered by this network ensures coverage of every critical vertical in our portfolio and fund exposure:

- Academic Experts provide visibility into groundbreaking innovations and technologies

- Discovery and Development Specialists focus on execution and translating early-stage technologies into next-generation therapeutics, medical devices, or diagnostics

- Clinical and Regulatory Advisors assist in navigating the rapidly evolving clinical and regulatory landscape

- Commercial Experts help us understand pharmaceutical decision-making processes and broader market dynamics affecting our portfolio companies

To complement this network, we have developed a next-generation research platform built around proprietary analytical software known as LABI (Luma AI Brain Initiative). This platform provides both our fund and our portfolio access to trillions of curated data points through an intuitive interface that significantly reduces diligence times while leveraging advanced meta-analysis and analytics, empowering us to uncover insights others typically miss.

With these foundational elements in place, Luma Group has strategically aligned its passion and fund lifecycle with the asset class and companies that are driving innovation. With a lot of passion, hard work, and some luck, Luma Group can drive meaningful improvements in patient outcomes within our lifetime.

- Pisano, G. P. (2006). Science Business: The Promise, the Reality, and the Future of Biotech. Harvard Business School Press. ↩︎

- Booth, B. L., & Zemmel, R. W. (2004). Prospects for productivity. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 3(5), 451–456. ↩︎

- Scannell, J. W., Blanckley, A., Boldon, H., & Warrington, B. (2012). Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 11(3), 191–200. ↩︎

- Deloitte Centre for Health Solutions. (2022). Measuring the Return from Pharmaceutical Innovation 2022: Balancing the R&D equation. Deloitte Insights. ↩︎

- DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G., & Hansen, R. W. (2016). Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. Journal of Health Economics, 47, 20–33. ↩︎

- Deloitte Centre for Health Solutions. (2022). Measuring the Return from Pharmaceutical Innovation 2022: Balancing the R&D equation. Deloitte Insights. ↩︎