Living with epilepsy can feel like walking in a minefield: patients often feel like they need to tiptoe through their lives, fearful that any misstep or obscure catalyst can trigger a (potentially deadly) seizure. In the non-epileptic brain, neuron ensembles operate with one another in precise and synchronized coordination, giving rise to normal cognition, perception, and movement. In many epilepsy cases, patients develop seizures after an injury or other insult (e.g., traumatic brain injury, stroke, tumors, etc.) induces a structural malformation in the brain, serving as the source of abnormal discharges between neurons that manifest as seizures. In other cases, mutations in a variety of genes can disrupt the normal balance between excitation and inhibition within neurons, representing direct genetic causes of epilepsy.

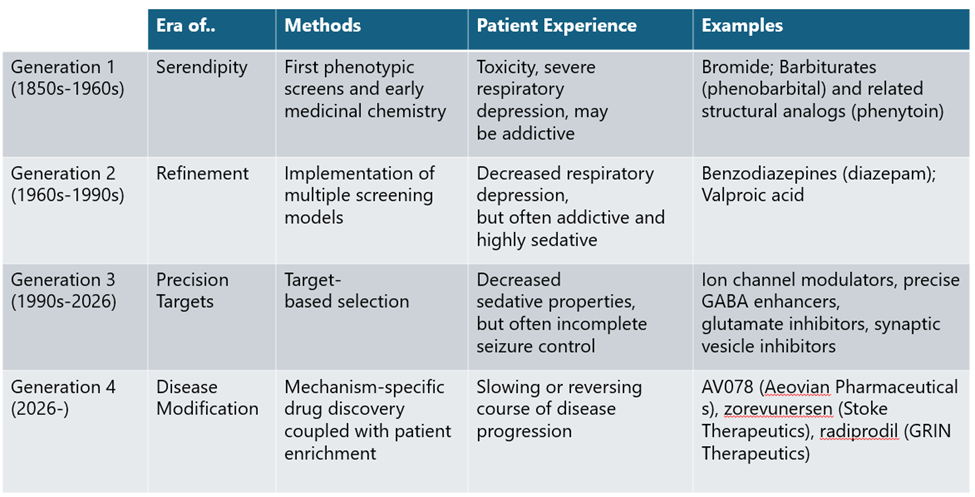

First discovered nearly 200 years ago, the original anti-seizure medications (ASMs) were blunt tools that muted neural activity across the brain. Since then, epilepsy and seizure care has changed dramatically, progressing from institutionalized epilepsy colonies and dangerous sedatives to daily oral pills with high molecular specificity. Despite more sophisticated methods of treating seizures, patients still lack the independence they deserve. Nearly 40% of patients are considered drug-resistant, and many more fail monotherapy and require a combination of multiple concurrent ASMs.

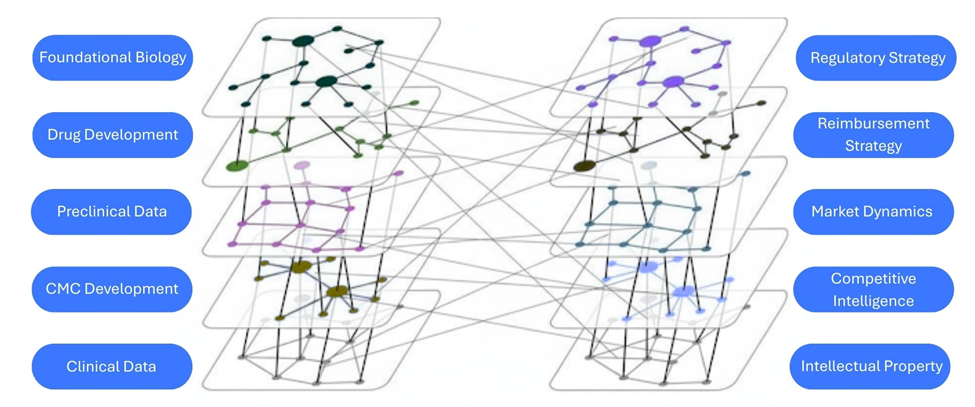

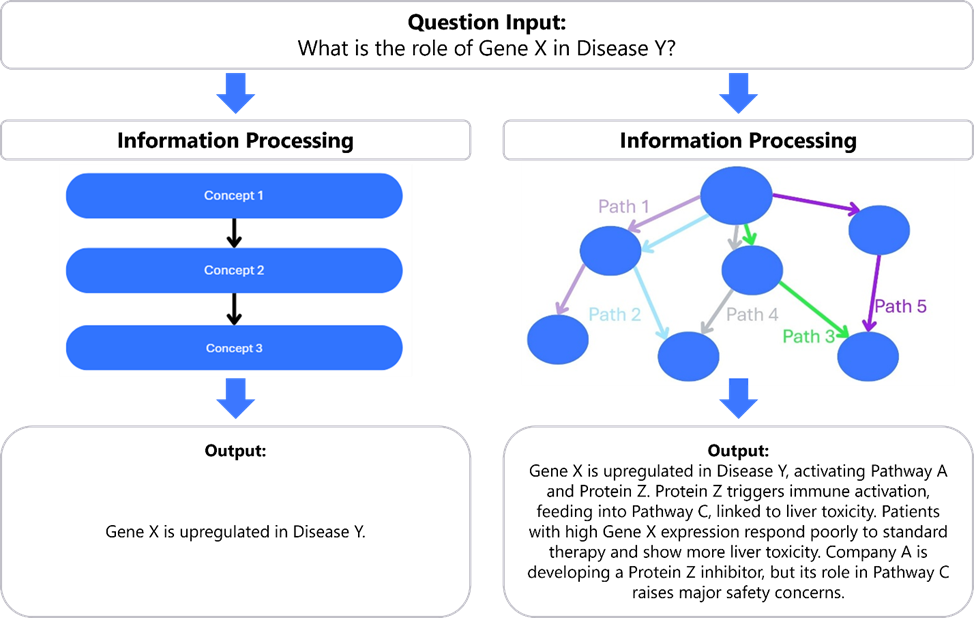

This paper traces the historical arc of epilepsy patient-experience and drug development, highlighting the limitations that have created a therapeutic ceiling for current ASMs. We then examine emerging disease-modifying strategies that move beyond “turning down the volume” of brain activity, including targeted mTORC1 inhibition in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), genetic medicines for developmental epileptic encephalopathies, neuroinflammation-directed therapies, and cell-based approaches to restore inhibitory balance.

These advances signal the potential beginning of a new era in epilepsy treatment, one focused not just on seizure suppression, but on modifying disease biology itself.

January 2026

What are Seizures? A Cacophony in the Brain

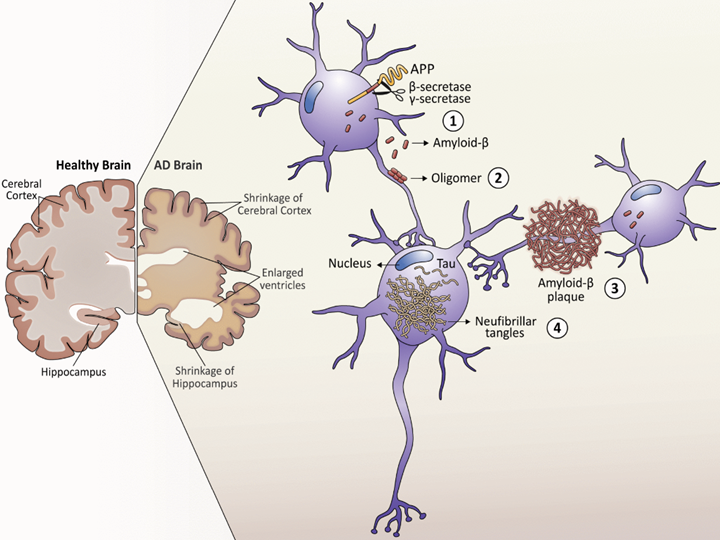

Normal brain function depends on the precise coordination of groups of neurons, or ensembles, that work together within neural circuits. In a non-epileptic brain, functions like movement and vision arise from the coordinated firing of many individual neurons, forming an ensemble. Much like sections of an orchestra operate in tight coordination to create harmony, neuron ensembles fire together with tight temporal precision to give rise to complex behavior. During a seizure, this harmony breaks down, and the ensemble makes a cacophony of noise instead: neurons become hyperexcitable, large networks fire synchronously, and electrical activity spreads in an uncontrolled manner.

Figure 1: Representative brain activity and clinical presentation of seizures.

Source: Beniczky S, Trinka E, Wirrell E, et al. Updated classification of epileptic seizures: Position paper of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2025. PMID: 40264351. and Sadiq MT, Akbari H, Rehman AU, et al. Exploiting Feature Selection and Neural Network Techniques for Identification of Focal and Nonfocal EEG Signals in TQWT Domain. J Healthc Eng. 2021. PMID: 34659691.

Early anti-seizure medications (ASMs) were potent sedatives that muted electrical activity across the brain, turning the volume of the brain orchestra to near zero. These blunt-force drugs silenced the brain much like epilepsy care of that era silenced epilepsy patients, who were commonly confined into “epilepsy colonies.” Institutionalization was justified in the name of patient and public safety—and “moral treatment”—as epilepsy patients were stigmatized as unreliable workers and a workplace risk due to the unpredictable nature of seizures. Seizure patients effectively lost their independence to constant confinement and the severe depressive side effects of sedatives. Since the closure of the last epilepsy colonies in the 1960s, modern ASMs have progressed from blunt force suppression to more targeted modulation of brain activity: instead of turning the volume down, the ASMs of today tune the orchestra to try to harmonize the brain. This combination of changing social norms and modern medicine has welcomed some independence for epilepsy patients.

However, the job is still not done. Nearly 40% of epilepsy cases are considered drug-resistant and many patients require multiple concurrent ASMs.1 Even in patients with adequate seizure control, the unpredictable nature of each event casts a shadow of fear and uncertainty that restricts patient independence. Epilepsy can restrict access to certain careers, requiring some individuals to medically retire or change professions despite being otherwise capable. Many patients live in fear of not knowing what will trigger a new seizure, making even leaving the house an unprecedented mental burden. When each seizure carries risk of severe injury—and in rare cases even death—the physical and mental trauma of each seizure turns epilepsy into a relentless, lifelong battle. The efficacy of contemporary ASMs has hit a ceiling, and patients are longing for a new age of disease modification.

Early Days: Moving from Serendipity to Empirical, Phenotypic Refinement

Early ASMs mirrored the blunt, empirical nature of 19th-century drug discovery.2,3 Bromide salts remained the primary treatment until 1912, when phenobarbital was serendipitously found to suppress seizures. These early therapies prioritized observable results over biological understanding, frequently trading seizure control for profound sedation and cognitive impairment. These early therapies reflected a trial-and-error approach to drug development, prioritizing observable effects over biological understanding and often trading seizure control for significant cognitive and physical impairment.

A turning point came in the 1930s with the introduction of animal seizure models, enabling systematic compound screening and giving rise to empirical drug discovery as it is practiced today. This approach led to the discovery of phenytoin and other first-generation ASMs through iterative chemical modification and phenotypic testing, though many retained barbiturate-like adverse side effects.

Generation 2 ASMs, including benzodiazepines introduced in the 1960s, followed a similar path but spared patients from the dangerous respiratory side effects of Generation 1 ASMs. While this was meaningful progress in ASM development, both generations of ASMs still broadly suppressed neural activity rather than targeting disease biology, a direct shortcoming of phenotypic screening. This limitation would not persist long, however, as GABA was soon identified as the cognate receptor for the benzodiazepine class of drugs, opening the door for precision, target-based drug discovery approaches.

Contemporary: Moving away from addictive molecules

The history of ASM drugs has mirrored the technological advances that are the foundation of modern drug discovery today. The identification of GABA as the target of barbiturates and benzodiazepines has given way to targeted, high-throughput screening for molecules that bind to a specific target that is known to be implicated in seizure activity.

While phenotypic screens (and serendipitous trial and error) still have a prominent role in the drug discovery process today, the current ASM landscape has expanded to include a diverse range of mechanisms that roughly fall into four different buckets:4

- Modulators of ion channels: This class of ASMs primarily aims to stop neural activity during seizures by modulating the flow of positively charged ions in or out of the neuron. As an action potential propagates in neurons, charged particles flow through the cell membrane to create an electrical gradient. An ASM targeting this flow of charged particles can ameliorate the hyperactive electrical activity of neurons that occur during a seizure. These ASMs can act on the various ion channels expressed in a neuron, as ASMs that act on sodium or calcium channels inhibit the flow of those ions into the cell, while potassium channel modulators attempt to increase the flow of ions outside of the cell.

- GABA-activity enhancers: Seizure activity can also be ameliorated by modulating the action of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. Pre-synaptic inhibitory neurons typically inhibit post-synaptic neurons by the action of GABA, which reduces spontaneous or bursting activity of an active neuron. Given the central role of neuronal hyperexcitability during seizure, enhancing the action of GABA is a proven mechanism of reducing seizure activity. Many of the first and second generation ASMs (the barbiturate and benzodiazepine classes) were later found to potentiate anti-seizure activity by activating the GABA receptor. In addition to directly acting on the GABA receptor, the GABA inhibitory pathway can be modulated by increasing the amount of GABA in the synapse or reducing the amount of GABA that is metabolized once it is produced.

- Inhibitors of synaptic excitation via glutamate modulation: While GABA is the canonical inhibitory neurotransmitter, glutamate is the canonical excitatory neurotransmitter. As a result, ASMs that act on the glutamate system aim to inhibit the glutamate receptors subtypes such as NMDA and AMPA. Inhibition of these receptors blocks the propagation of further action potentials on the post-synaptic neuron, dampening the probability of seizure initiation.

- Modulators of neurotransmitter release: Another method of altering neuronal activity in seizures is by targeting the regulation of synaptic release of neurotransmitters. Compared to the other mechanisms, this is more nuanced and complex but has produced one of the best-selling ASMs to date in levetiracetam. Drugs that target SV2A and the alpha-2-delta-2 calcium channel subunit work by slightly reducing the efficiency of neurotransmitter release, especially in a hyperactive neuron that is firing very quickly.

Given the long history of epilepsy drug discovery, there are numerous options available to patients today, and patients are treated according to their classification of epilepsy. Each patient can be systematically triaged into different treatment paradigms that are determined by the clinical presentation of their seizures. However, nearly all ASMs are still not disease-modifying therapies: up to 40% of patients fail monotherapy5 and up to 25-30% of patients are treated using multiple ASMs.6

Figure 2: Mechanisms of contemporary anti-seizure medications.

Source: Loscher W, & Klein P. The Pharmacology and Clinical Efficacy of Antiseizure Medications: From Bromide Salts to Cenobamate and Beyond. CNS Drugs. 2021. PMID: 34145528.

Next Generation: Novel Approaches of Disease Modifying Therapies

As investors in the next generation of biotechnology companies, we believe this is the beginning of the golden age of seizure control. The current era of ASMs may have hit a ceiling, but our understanding of the complex and multifaceted biology of epilepsy has continued to expand. Instead of viewing the entire orchestra as out of tune, we now have an unprecedented view into several subtypes of epilepsy that tell us that only specific instruments have gone awry, giving the perception that the entire orchestra of the brain is dysfunctional in these patients. Until now, ASMs have only suppressed or tuned brain-wide neural activity. The next generation of ASMs will leverage novel technologies and tools to precisely repair, replace, or remove the instruments playing out of rhythm with the rest of the orchestra.

Like many therapeutic areas, the holy grail in epilepsy and seizure control is a disease modifying drug that stops or reverses the course of the disease. Broadly across the wide range of epilepsies, there are many underlying mechanisms that are still not clearly defined, and up to 70% of diagnosed epilepsies are of unknown cause. But this tide is beginning to shift, opening the door for true disease modifying options that target the underlying causes of seizures. For example, the developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DEEs) are a group of epileptic disorders that often have well-defined genetic underpinnings, and include indications like Dravet syndrome, Rett Syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). Given our current understanding of epileptogenesis and related disorders, there are several areas of opportunity that we are watching closely and excited about the prospect of bringing disease modifying solutions to patients:

- Inhibiting the mTOR pathway in TSC: Throughout the epilepsy literature, TSC is widely cited as an indication that is most tractable to disease modifying therapies.3 Seizures in TSC patients are caused by growth of benign tumors and excitation/inhibition imbalance due to overactivation of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) directly caused by TSC mutations. Previously developed mTOR inhibitors such as rapamycin and everolimus are known to non-selectively target both mTORC1 and mTORC2 and are traditionally indicated for certain cancers and for immunosuppression of organ transplant patients to prevent host rejection. Use of the non-selective mTOR inhibitor everolimus in TSC has been associated with high rates of dose-limiting adverse events, restricting many patients to low doses and exposure levels that may have limited efficacy. Aeovian Pharmaceuticals, a Luma Group portfolio company, has been working to tackle the medicinal chemistry challenges that give rise to the dose-limiting adverse events frequently seen with nonselective mTOR inhibitors in patients, and is now entering Phase 2 clinical trials with a selective mTORC1 inhibitor that is CNS penetrant and capable of higher drug exposures than is achievable with current rapamycin analogs.

- Genetic medicine in DEEs: Because the genetic underpinnings of DEEs are often well defined, these indications are synergistic with genetic medicines. This is especially true for disorders caused by loss-of-function mutations (e.g., STXBP1- or SYNGAP1-related disorders), where delivery of a functional gene fragment can supplant the missing protein’s functionality. However, some mutations and proteins require more sophisticated approaches, such is the case with MECP2 protein expression in Rett Syndrome. Both loss-of-function (Rett Syndrome) and gain-of-function (MECP2 duplication syndrome) mutations of MECP2 are associated with disease, and protein levels must be tightly controlled within a “goldilocks” window that maintains nontoxic levels.7 There are also creative approaches to avoid gene therapy altogether, such as zorevunersen (Stoke Therapeutics) that is currently in registrational Phase 3 trials for Dravet Syndrome, an autosomal dominant haploinsufficiency that only has one functional copy of the SCN1A gene. Here, the company’s proprietary TANGO platform upregulates the functional SCN1A gene to restore normal protein expression levels.

- Emerging hypotheses in neuroinflammation: Neuroinflammation has become an area of intense research in other neurological disorders, and its link to epilepsy is beginning to emerge as well. Several case studies have highlighted the efficacy of the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra in new-onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) and febrile-infection related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES). In these very severe cases of status epilepticus, clinicians have noted that anakinra can be advantageous to use in chronic refractory patients to reduce seizure frequency following onset of status epilepticus.8 Anakinra is now commonly used as a second line therapy for NORSE.9 In line with the neuroinflammation hypothesis, a recent study highlighted the potential of using JAK inhibitors in treatment-refractory mice.10

- Cell therapy approaches: Inhibitory GABAergic neurons play an important role in regulating hyperexcitable activity during seizure activity, and adoptive cell therapies to introduce more of these neuronal cells is an interesting therapeutic approach to address this need. Neurona Therapeutics is advancing an inhibitory neuron cell therapy, following the early promising results of similar cell therapy approaches used in Parkinson’s disease.

The Investor’s Perspective: A Decade of Impact

Over the course of nearly 200 years, the epilepsy patient community has seen significant strides in how we view and treat seizures. The medical community has done away with the epilepsy colonies and patients are no longer subject to addictive sedatives that do more harm than good. As our understanding of disease mechanisms and biology have evolved, so too has our ability to treat the disease, beginning with targeted based approaches that modulate the canonical neurotransmitter pathways involved with neuron excitability. However, these approaches have been symptomatic therapies at best, and many patients are being left behind.

In this next decade of seizure management, we welcome—and fervently support—the disease modifying approaches that target the known, core drivers of epilepsy. Novel biological insights into certain epilepsy patient populations have identified which instruments are playing out of tune or rhythm with the rest of the orchestra, and we are beginning to leverage novel chemistry to repair, replace, or remove those instruments. We also have the advantage of decades of high quality clinical trial execution, giving us the infrastructure to identify and enrich for patients who have specific subtypes of epilepsy that will respond to disease modifying treatments. We are on a precipice, about to turn a corner to forever leave sedative and ineffective medicines behind. Over 3 million patients are living with epilepsy in the U.S., and the moment has arrived to bring huge clinical impact to each of these patients.

- Sheng J, Liu S, Qin H, et al. Drug-Resistant Epilepsy and Surgery. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018. PMID: 28474565. ↩︎

- Rho JM & White HS. Brief history of anti-seizure drug development. Epilepsia Open. 2018. PMID: 30564769. ↩︎

- Loscher W & Klein P. The Pharmacology and Clinical Efficacy of Antiseizure Medications: From Bromide Salts to Cenobamate and Beyond. CNS Drugs. 2021. PMID: 34145528. ↩︎

- Klein P, Kaminski RM, Koepp M, et al. New epilepsy therapies in development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2024. PMID: 39039153. ↩︎

- Hakami T. Efficacy and tolerability of antiseizure drugs. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021. PMID: 34603506. ↩︎

- Lee JW & Dworetzky B. Rational Polytherapy with Antiepileptic Drugs. Pharmaceuticals (Basal). 2010. PMID: 27713357 ↩︎

- Clarke AJ, & Sheikh APA. A perspective on “cure” for Rett syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018. PMID: 29609636 ↩︎

- Wickstrom R, Taraschenko O, Dilena R, et al. International consensus recommendations for management of new onset refractory status epilepticus including febrile infection‐related epilepsy syndrome: Statements and supporting evidence. Epilepsia. 2022. PMID: 35997591. ↩︎

- Hanin A, Muscal E, Hirsch LJ. Second-line immunotherapy in new onset refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2024. PMID: 38430119. ↩︎

- Hoffman OR, Koehler JL, Espina JEC, et al. Disease modification upon 2 weeks of tofacitinib treatment in a mouse model of chronic epilepsy. Sci Transl Med. 2025. PMID: 40106581. ↩︎